When Shoprite opened its first Nigerian store in 2005, it looked unstoppable. The South African retail giant was bringing modern hypermarket shopping to West Africa’s largest economy, complete with imported goods, sprawling aisles, and the promise of a “world-class” retail experience.

Fast forward to 2024, and Shoprite’s Nigerian stores are shells of their former selves—empty shelves, unpaid suppliers, and frustrated customers. Meanwhile, a startup called Bokku that launched just two years ago has exploded to 124 locations and is rewriting the rules of African retail.

This isn’t just a story about one company winning and another losing. It’s a masterclass in how to build for emerging markets—and how even experienced players can spectacularly misread the room.

The Fall: How Shoprite Lost Nigeria

Shoprite’s problems started long before the pandemic. By 2020, the company was hemorrhaging money in Nigeria, reporting translation losses of R488 million as the naira collapsed against the rand. The bigger issue? They couldn’t get their money out.

“We couldn’t repatriate profits,” a former executive explained. Nigeria’s Central Bank had essentially cut off dollar access, trapping Shoprite’s local earnings in a depreciating currency. Every month they operated, they were losing value.

But the foreign exchange crisis was just the most visible symptom of a deeper problem: Shoprite had brought the wrong business model to Nigeria.

The Million-Dollar Mistake

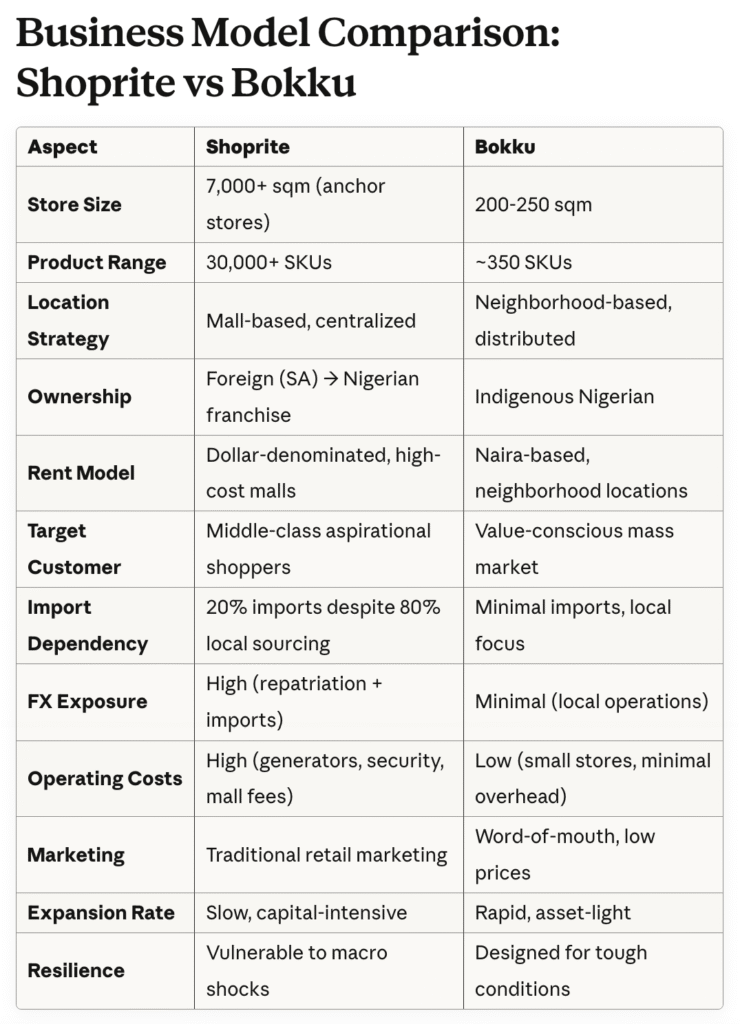

Here’s what killed Shoprite in Nigeria: they built stores averaging 7,000+ square meters in expensive malls, targeting the same middle-class shoppers who made them successful in South Africa. The problem? That demographic barely exists in Nigeria, and the ones who do exist were rapidly getting poorer.

The company’s massive stores required dollar-denominated rent, expensive generators (because electricity is unreliable), and constant imports to stock shelves with products Nigerian suppliers couldn’t provide. Even though they sourced 80% locally, that remaining 20% became fatal when import costs exploded and the naira crashed.

Then came the perfect storm: xenophobic attacks in 2019, a recession, COVID-19, and accelerating inflation that peaked at 33.95% in May 2024. By the time Shoprite Holdings sold out to Nigerian buyer Persianas Investment for $73 million in 2021, the brand was already broken.

The new owners? They somehow made things worse. Today, Shoprite stores in Lagos, Abuja, and other cities are notorious for empty shelves and supply chain chaos. The company has shuttered locations in Kano, Ilorin, and Ibadan, while owing suppliers hundreds of millions in unpaid invoices.

The Rise: Bokku’s Brilliant Bet

While Shoprite was collapsing, entrepreneur Adewale Adeyemi was studying a completely different playbook: German hard discount retail.

In September 2022, right as Nigeria’s economic crisis was intensifying, Adeyemi launched Bokku with a radical proposition: what if you took the Aldi/Lidl model—limited selection, everyday low prices, no-frills operations—and dropped it into Lagos?

The results have been stunning. In just over two years, Bokku has grown to 124 stores and is adding locations faster than any retailer in Nigerian history.

The Model That’s Working

Walk into a Bokku store and you’ll immediately notice what’s missing: the sprawling aisles, the thousands of product choices, the fancy fixtures. A typical Bokku is just 200-250 square meters—about 3% the size of a Shoprite anchor store—and stocks roughly 350 SKUs versus the 30,000+ in a traditional supermarket.

But here’s what they do have: prices that are 15-30% below market. Indomie noodles for N190 instead of N250. Cooking oil for N2,700 instead of N3,000. Golden Penny pasta for N900 versus N1,100 everywhere else.

The signature product? Fresh-baked bread at N1,250 that local resellers can buy in bulk and flip for N1,500. Bokku hired 200 bakers in 11 months just to keep up with demand, and customers line up multiple times daily to grab hot loaves.

“We’re not trying to be everything to everyone,” Adeyemi has said. “We’re trying to be the most affordable option for everyday essentials.”

Why It’s Working: The Five Key Advantages

1. Hyperlocal Accessibility

While Shoprite built in malls that required car ownership, Bokku is putting stores within 2 kilometers of customers—walking distance. They’re focused on the Lagos mainland, where most of the city’s 20+ million people actually live, not the bougie islands where expats hang out.

No transportation costs. No time wasted in traffic. Just walk down the street.

2. Radical Price Leadership

By limiting SKUs, buying in bulk, and focusing on private label and local brands, Bokku has pricing power that traditional retailers can’t match. They’re playing the Costco game: make pennies per item, make it up in volume.

3. Zero Foreign Exchange Exposure

This is huge. Because Bokku is Nigerian-owned and sources almost entirely from local suppliers, they have minimal dollar exposure. When the naira crashes, their costs and revenues move together. No trapped profits, no repatriation issues, no import nightmares.

4. Asset-Light Expansion

Small stores mean Bokku can open five locations for the cost of one Shoprite. They’re paying naira-based rent on neighborhood buildings, not dollar-denominated leases in luxury malls. If a location underperforms, it’s easy to close. The model is built for speed and flexibility.

5. Understanding the Informal Economy

Perhaps most importantly, Bokku gets Nigeria. They know that many of their customers are resellers who need to buy products they can mark up. The bread model isn’t just about selling bread—it’s about creating a symbiotic ecosystem where small entrepreneurs can make money, which brings them back every day.

The Breakdown: Why One Model Died and Another Thrived

Let’s be clear about what happened here: this wasn’t about execution quality or management competence. Shoprite ran a perfectly fine South African retail operation. The problem was they brought a South African solution to a Nigerian problem.

What Shoprite Got Wrong:

They assumed Nigerian consumers wanted what South African consumers wanted: variety, experience, aspiration. They built for stability in a volatile market, for affluence in an impoverished economy, for car owners in a city where most people take buses.

Every strategic decision—big stores, mall locations, imported goods, dollar-denominated costs—made sense if you were building for the Nigeria you wanted to exist, not the Nigeria that actually exists.

What Bokku Got Right:

They built for the Nigeria that is: price-sensitive, cash-strapped, transportation-challenged, and value-obsessed. They didn’t try to change consumer behavior; they designed around it.

More importantly, they launched at exactly the right time. As inflation soared and purchasing power collapsed, Nigerians stopped caring about shopping “experience” and started caring exclusively about price. Bokku was there with the answer.

The Bigger Picture: What This Means for African Tech and Retail

The Shoprite-Bokku story has implications far beyond grocery retail.

First, it’s a reminder that local knowledge and local ownership matter enormously in emerging markets. Adeyemi didn’t need to learn about naira volatility or Lagos transportation patterns—he lived them. That cultural fluency is a real competitive advantage.

Second, it shows that the right business model beats the biggest brand. Shoprite had 16 years of brand recognition, hundreds of millions in sunk costs, and the backing of a multinational corporation. Bokku had a founder, a good idea, and perfect timing. The good idea won.

Third, it demonstrates that in crisis markets, boring businesses can beat sexy ones. There’s nothing particularly innovative about Bokku’s model—Aldi invented it 100 years ago. But applying proven models intelligently to new markets is its own form of innovation.

What Comes Next

Bokku isn’t without risks. The company is expanding so fast that supply chain management will become increasingly complex. They’ll need to maintain quality as they scale to 200+ stores. And competitors are already copying the model—indigenous players like Justrite and Market Square are launching their own discount formats.

There’s also the question of whether Bokku can expand beyond Lagos. The Lagos model works because of population density and the existing informal retail ecosystem. Will it translate to Abuja? Port Harcourt? Kaduna?

As for Shoprite, the company has announced a “reset” strategy with smaller stores and more local sourcing. But with empty shelves, angry suppliers, and a damaged brand, the path back looks nearly impossible. Sometimes you don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.

The Lesson

If you’re building for emerging markets—whether it’s retail, fintech, logistics, or anything else—the Bokku playbook offers a clear lesson: don’t build for the market you wish existed. Build for the market that does exist.

Understand the constraints your customers actually face. Design around them, not against them. And when everyone else is building big, expensive, and complicated, consider whether small, cheap, and simple might actually win.

In Nigeria’s retail revolution, the winner wasn’t the company with the biggest stores or the longest track record. It was the company that understood what Nigerians actually needed: affordable food, close to home, right now.

That’s not aspirational. But it is profitable. And in business, profitable beats aspirational every single time.